Not so many moons ago, I was setting up a peer assessment activity. with a class of fifteen year olds. ‘Abbie, could you do Kris, please?’ ‘Isiaah, you do Henry.’ Shayla, you can choose whether you want to do Mike or Bethany – or both’

Like any reasonable adult, I began snorting at my own inadvertent piece of genius witticism about halfway into the second instruction.

‘You’re such a child, Miss,’ chasisted one, eyes heavenward, which served only to open the floodgates for more cackling before I could re-compose myself enough to get on with the business at hand.

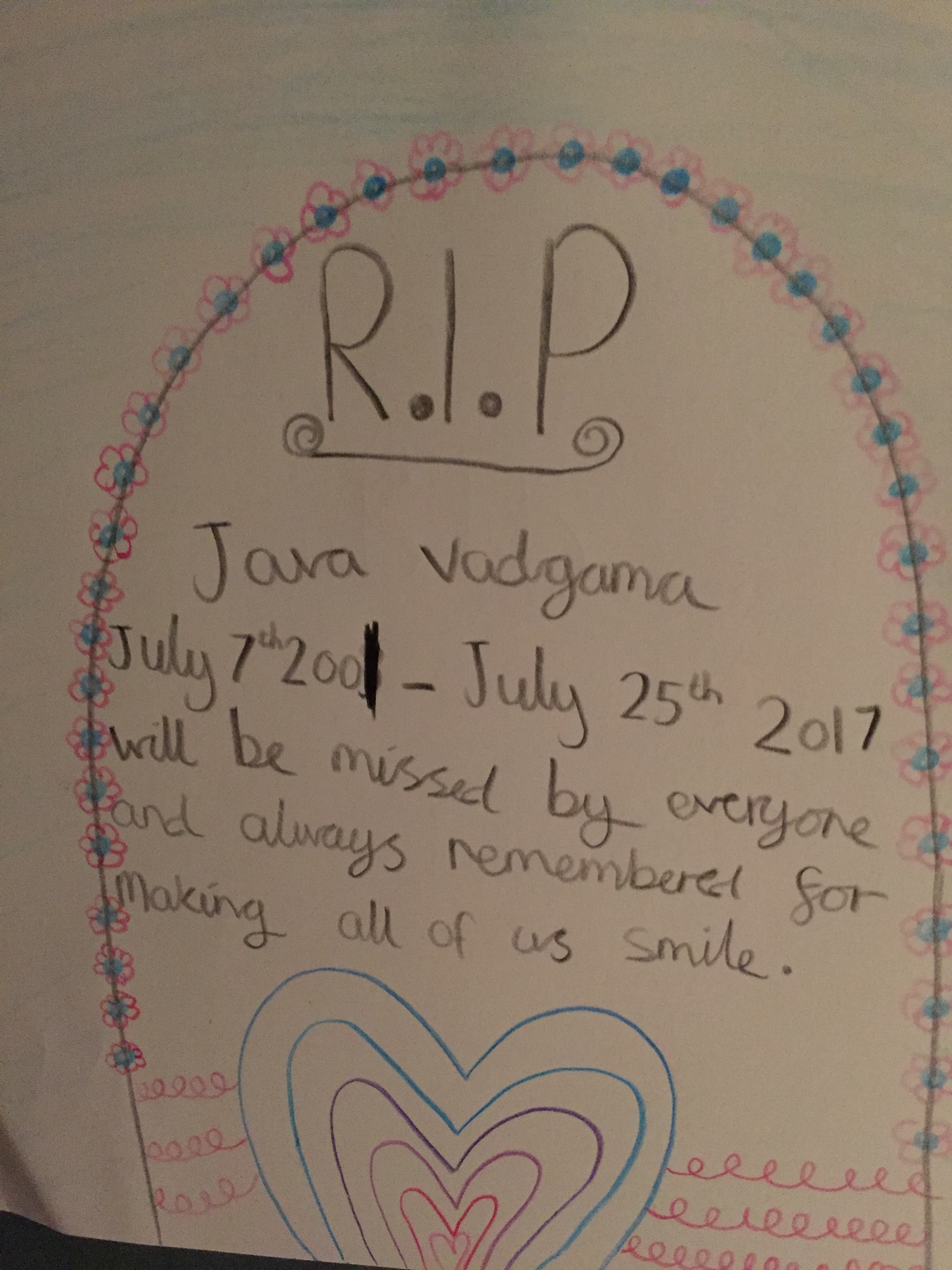

More recently, at home, we lost our dear old rickety cat. My ten year old was there when the vet made the kindest possible decision to end her suffering. My daughter held her paw as Java passed away. There is, I was saying to a colleague yesterday, something so honest, pure and quite inspirational about her grief. It comes in waves – spying a brand of coffee with the same name as the cat; the moment before bed when the cat would curl up. My inexplicably stylish child even does grief with panache. The cat has a grave covered in scatter-crystals and festooned with yellow roses and coloured windmills.

Children have a way of opening my eyes and making me see the world from different angles.

On a less positive note, in schools here is a phenomenon which I myself frequently discuss with an air of wistfulness. Forgive me if this is overly simplistic, but I have noticed a pattern which points to a uniquely challenging reality for teachers in the UK: teachers have to earn students’ respect before quality learning can happen. Teachers from Canada, Australia, German, Spain and France have regularly commented on this – where they come from, if a child fails an exam, the responsibility lies firmly with the child. I’ve met several versions of the teenager in Germany who is re-sitting the school year for the second time, who looks somewhat ashamed at his lack of commitment.

As teachers country-wide steel themselves for possibly the scariest set of exam results in recent history (so many unknowns!), they will already be drafting, at least in their heads, their exams analysis, their interventions and their actions. ‘What can WE do better or differently?’ will be the theme sung by teachers around many departmental tables in September, to the tune of beaten chests and vows to commit hari kari if Standards Don’t Rise.

Students autonomy, independence, ownership of learning – the valuing of academic success in its own right, without the stickers and bells – is a bloody tough nut to crack, and I’d be bold enough to suggest that there isn’t an action plan in the country that doesn’t include this somewhere near the top.

But there’s something else at work here. Like any phenomenon, when held up the light, there is something positive to be drawn from it – and it’s a question of balance.

Children should automatically respect adults – of course they should. They should stand in awe of our life’s experience, our wisdom and the sheer gravitas which propelled us to the greatness that is teaching Year 9 quadratic equations. Children should know, through sheer instinct, that the consequences of failure to try in school could be catastrophic.

The thing is, it doesn’t quite work like that at the chalkface. Learning is a risky, scary business and children learn best when they feel safe enough to take risks – but not so safe that they become complacent or lazy. It’s about balance, again.

In all the schools where I’ve ever worked, respect has to be earned – and respect has to go both ways. Learning is the same – acknowledging, as a teacher, that we learn something new about ourselves, our proteges and the world ever time we interact with a child is actually quite a joyous thing, I find. I learn something new every time I step into a classroom or converse with a child about the world, and I am all the richer for it.

A colleague recently told me that, after establishing expectations of the students in her classroom, she flipped the question: ‘what do you expect from me?’ Students are remarkably incisive when talking about their learning experience. Having asked this question myself, the answers range from, ‘to mark my book regularly’ to ‘to tell my Mum if I’m doing well’ to ‘to treat us in a way that is fair’.

I love the fact that Ofsted now places such a weight on student voice. Students will tell you exactly as it is. These are a few gems from speaking to teenagers of friends of mine. ‘I know Sir won’t laugh at me if I find it difficult’, ‘I like it when Miss asks me to read allowed’ ‘I like strict teachers – it shows they care.’ Or, ‘My teachers doesn’t plan his lessons,’ ‘I’m scared to say I don’t understand’ and ‘it’s clear that she doesn’t like children – why is she a teacher?’

Through my research, teachers have cited numerous examples of how they’ve ‘exposed’ themselves as learners in the classroom: from offering rewards to students who can teach me new words to taking careful note of the essay in which one of the students said he was struggling to copy with exam stress.

Saying sorry is also important – from making a joke of putting the wrong year on the board (my ‘deliberate’ mistake) to overlooking a child’s distress or eagerness to contribute to spilling dinner on their exercise book – saying sorry doesn’t cost anything. And when they help you do something better – ‘I listened to what you said and so I’ve planned this activity to help you’ can be great practice.

To be clear: I am no advocate of over-matiness with students – they need us to be adults; not their friends. As Mr Drew points out in the always-brilliant Educating Essex, it’s in the job description of young people to get it wrong – to make mistakes – and it’s our job to steer them in the right direction and help them locate their moral compass.

Nor do I advocate a situation where the students feel they ‘rule the roost’ – amidst the humour and the warmth of the classroom, clear boundaries are essential – as they’ve told us, students need them and appreciate them. So the student who takes it upon him- or her-self to mess with the seating plan or the one who refuses to spit out their gum can expect VERY short shrift. There are occasions when listening to what a student has to say isn’t appropriate – when they simple need to admit that they’re in the wrong. And the line ‘you’re not in charge!’ gets plenty of use both in my classroom and my house.

And, when I reflect on my earlier years of teaching, when I gave and gave to my students, I have had some difficult conversations with myself – did being ‘there’ so much lead to an over-dependence on teachers which put some of those young people on a difficult track when the realities of adulthood hit? And do we, in some of the best schools, risk a ‘culture of personality’ where students will actively select the teachers they ‘will behave with’ – and those with whom they simply ‘won’t’…

I’m also acutely aware, like all teachers, that the new era of 100% terminal exam means that real student independence is more important than ever; no longer can we hold their hands through the intensity of assessment in any way. Nobody will ask us for references about the students, or about their finest hour in the classroom. In fact, we teachers aren’t even allowed in the exam hall, because we might have developed a complex blinking cheat-system or something.

Nevertheless, education is about more than exams, and, in our quest to give children the best possible futures, relationships are key. As teachers, we must represent authority and model the patience and courtesy we expect from our student. But we must also model humility, fallibility and a desire to be better than we are. As well as supporting pupil-teacher relationships, we need to help students to trust one another and support one another: ‘we succeed or fail together’ is one mantra I’ve heard used.

Meaningful and productive teacher-pupil relationships aren’t born overnight. They take weeks of training and re-iteration and dog-with-a-bone stubbornness. But, for their richness, they are worth it for all concerned. At best, they will form the blueprints for future relationships at home and at work, and where trust is built, we stand a greater chance of helping them overcome life’s obstacles.

Ultimately, perhaps it’s about empathy – I do wonder (and I’m sure there’s a clever philosopher somewhere who will know more) if we are our purest and most raw ‘selves’ at 13. There has always been something about Year 9 that has both driven me to sleepless nights with frustration and stolen my heart. These are the students who will tell you where exactly to stick your carousel activity then cry when you leave the school.

I do suspect that those of us who can’t imagine doing any other job have our own inner adolescent. I know that the fear, frustration and rage of my students is something that is quite visceral. I can relate their brooding blackness, their searing sense of injustice and their toilet humour

I know one thing for sure – as a wise friend once said, children ‘act out’ for a reason – because they have a message for the world and it is usually a request for help. It is extremely rare that a child acts out of malice. But they do have high standards and high expectations of their teachers – they expect integrity, commitment and respect, and a laugh goes a long way too.

Rest in peace, old cat, and in the assurance that you are being mourned beautifully.